How Big Is the Grand Canyon—and Why Is It So Famous?

America’s 13th national park is arguably its most famous and iconic. Spanning 1,218,375 acres (National Park Service), it’s the third-largest national park in the lower 48 states, behind Death Valley and Yosemite. The Colorado River Basin stretches as far north as Wyoming, with various tributaries merging as the river flows through Colorado, Utah, and northern Arizona before carving the Grand Canyon. To truly See, Hike, and Survive the Grand Canyon, it helps to understand the forces that shaped it: before it was partially tamed by multiple dams, the immense power of the Colorado River eroded the canyon wider and deeper—up to 18 miles at its widest point. In places, the canyon is over a mile deep, revealing metamorphic rocks around 1.7 billion years old at its base (U.S. Geological Survey).

How to Get to the Grand Canyon

Getting to the canyon almost always involves a long drive, especially if you’re flying in from an international airport. If, like 90% of visitors, you’re heading to the popular South Rim, here are your options:

- Las Vegas: ~4 hours 20 minutes west

- Phoenix: ~3.5 hours south

To the north, Salt Lake City is almost 7 hours from the lesser visited North Rim.

There’s enough to do and see to justify a multi-day stay—especially for hikers. But given the park’s distance from major cities and its proximity to Utah’s national parks, many travelers include the Grand Canyon as part of a larger Southwest road trip (see bottom of page for itinerary ideas).

When to Visit the Grand Canyon

South Rim: Open year-round, though winter conditions can bring snow and ice—especially at higher elevations.

North Rim: Approximately 1,000 feet higher than the South Rim, it typically closes in mid-October and reopens in May due to snowpack.

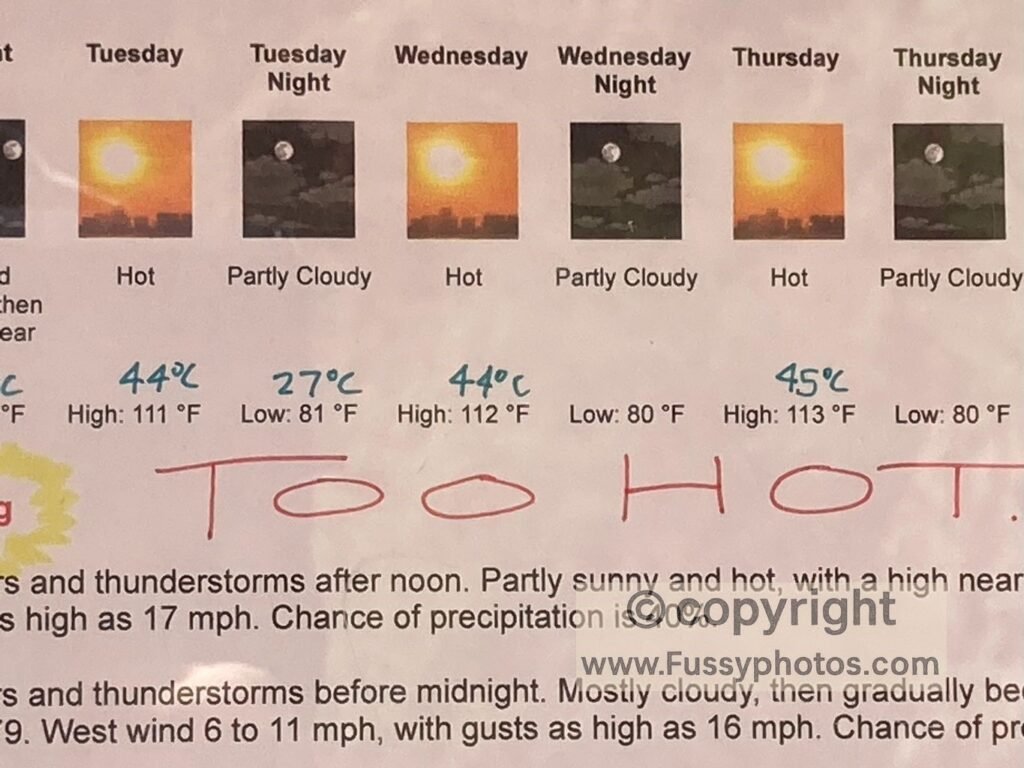

While summer is arguably the most uncomfortable time to hike in the canyon, I’ve had great experiences despite the heat. (See my linked South Kaibab–Bright Angel Trail hike below.)

Grand Canyon Helicopter Views and South Rim Sunrises — My First Visit

My first visit to the Grand Canyon came before my hiking days. I took a helicopter ride over the canyon, marveling at its enormous size and endless labyrinth of tributary canyons.

I also captured sunrise and sunset photos from the rim—an unforgettable introduction to its scale and beauty.

Grand Canyon Rim Trail vs. Hiking Into the Canyon

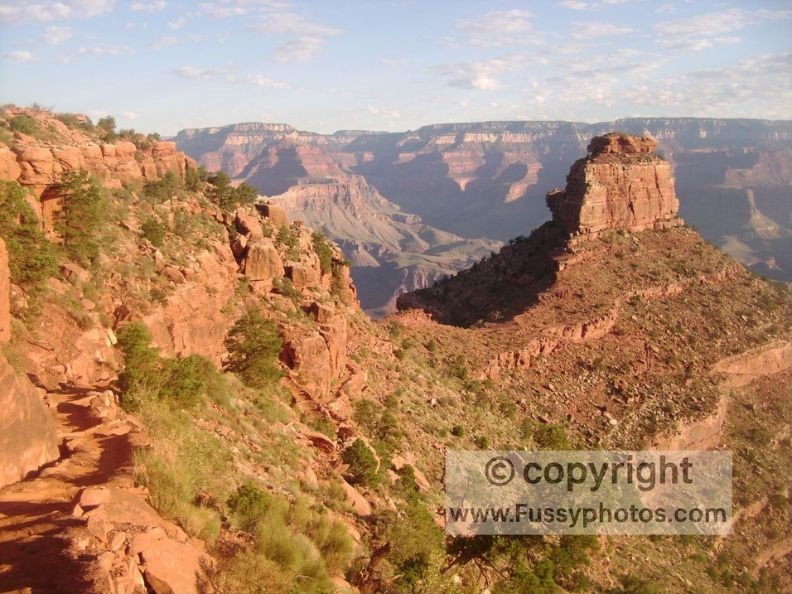

Walking the rim offers a breathtaking overview of the canyon’s vast width, but to truly experience its scale, you have to hike into it—feel its depth, trace its contours, and watch the rock layers change. It wasn’t until my second trip to the Grand Canyon that I discovered this first-hand.

South Kaibab Trail Grand Canyon — My Second Visit

My second visit was more adventurous. I hiked the South Kaibab Trail a little further than The Tip-Off, where panoramic views of the inner gorge and the Colorado River first come into sight.

I returned to the rim energized, already planning a return trip to reach Black Bridge—a suspension bridge connecting the North and South Kaibab Trails—and the river itself. That hike would become a loop, combining the South Kaibab and Bright Angel Trails (see below).

Grand Canyon Rim-to-River-to-Rim Loop: See, Hike, and Survive the Grand Canyon via South Kaibab and Bright Angel Trails

Grand Canyon Hiking Safety: Know Your Limits Before You Go

It goes without saying that you need to know your limits if you are descending into the canyon. The National Park Service (NPS) states that you should not hike beyond Cedar Ridge as a summer day hike on the South Kaibab Trail, and they also make it clear that over 250 people are rescued from the canyon each year.

If you haven’t trained for it and haven’t hiked in the canyon before, then attempting the full South Kaibab to Bright Angel loop is not for you. That said, you can still enjoy a section of the trail — but it’s important to recognize that the combination of extreme heat, massive elevation loss, and relentless gain make this unlike all other hikes.

I’ve been to the bottom of the canyon and back up twice. It’s a huge physical test, not just because of the elevation gain from the river — 4,500 feet on Bright Angel Trail, 4,700 feet on South Kaibab, and 5,700 feet on North Kaibab (there’s no easy way out!) — but because of the sheer heat you will experience as you descend then ascend and the toll this puts on your body.

NPS advises that you eat twice as much as you normally would, with a focus on salty snacks, water, and sports drinks. Despite this knowledge, and the fact that I had trained hard, started at dawn, and did most of the right things, the first time I did this hike I struggled coming back up and out of the canyon, having made three big mistakes.

Grand Canyon Hiking Mistakes: 3 Lessons Learned to Safely See, Hike, and Survive the Grand Canyon

The first mistake: I reached the canyon floor in good time (before 10 a.m.) and rested—but I began my ascent too early, at 10:30 a.m., precisely when you don’t want to be hiking. In summer, the canyon and its tributaries absorb sunlight into their walls and radiate it back like a furnace. As you descend, the NPS notes that “in general, temperature increases 5.5°F with each 1,000 feet of elevation loss.” At the bottom, temperatures can reach as high as 50°C (122°F)

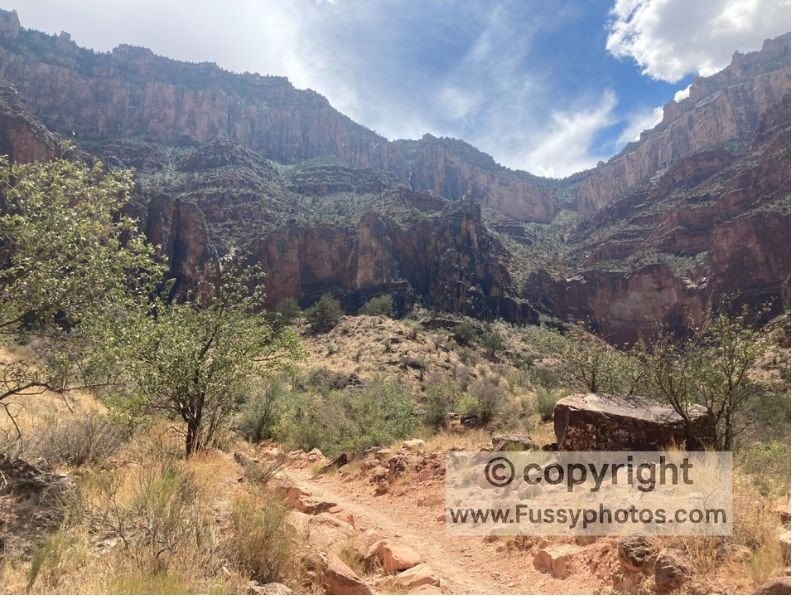

As I followed Pipe Creek along the Bright Angel Trail, it felt every bit this hot, and I felt terrible as I made my way up Devil’s Corkscrew (the switchbacks out of this section of canyon). By the time I reached Havasupai Gardens, I was uncomfortable and drank too much water trying to compensate.

Havasupai Gardens Misstep: Hydration Gone Wrong

That was my second mistake. Hyponatremia is a condition caused by diluting the sodium already in your bloodstream. Symptoms include nausea, confusion, and headaches.

After Havasupai Gardens, the Bright Angel Trail gains a comparatively gentle 600 feet in 1.2 miles before switchbacks take you up an almost sheer wall of the canyon, gaining 2,400 feet in 3.5 miles. My third mistake was leaving Havasupai Gardens too soon in the afternoon and hitting these switchbacks mid-afternoon.

Ascending this massive wall, I was suffering from the exertion when a hiker asked how I was. I explained that I had plenty of water but needed some sugar. Having eaten most of my lunch and with only water left, I had nothing suitable. He pulled out a bag with enough snacks for a whole family and kindly offered me some. Five minutes later, I felt noticeably better — though with a better strategy, I wouldn’t have needed the support of others.

I still had a great hike, but it’s best to be honest about what did and could go wrong. The key to a successful hike at the Grand Canyon — or indeed in any desert conditions — is preparation and meticulous planning. Much of my preparation was excellent, but some aspects simply weren’t good enough.

A year later, I returned at the same time of year, in the same conditions, and completed the same hike (this time with my partner). We had a fantastic time and I felt much better throughout the hike. If you’re curious what changed — and how to make your own rim‑to‑river‑to‑rim attempt safer and more enjoyable — the full breakdown is below.

How to Successfully Hike the Grand Canyon Rim‑to‑River‑to‑Rim Loop — What I Did Differently a Year Later

How the Grand Canyon Fits into a Road Trip

All drive times from Grand Canyon Village, South Rim:

Heading north opens up Utah’s Mighty 5, a collection of national parks that link naturally with a Grand Canyon visit. From Zion’s slot canyons to the red‑rock arches and high‑desert mesas farther east, each park adds its own flavour to a multi‑day Southwest loop.

Zion National Park (Springdale Visitor Center) — About 4.5 hours north – Hike iconic trails like Angels Landing or The Narrows, and enjoy Springdale’s relaxed basecamp vibe. If you’re looking for a multi‑day backcountry route to pair with the Grand Canyon, my Zion Traverse guide covers a spectacular 37‑mile journey from Kolob Canyons to Angel’s Landing.

Bryce Canyon National Park — About 5 hours northeast – Walk among thousands of hoodoos glowing orange and pink at sunrise, with short trails like Navajo Loop and Queen’s Garden offering unforgettable views.

Capitol Reef National Park — Around 5 hours northeast – Explore the Waterpocket Fold, orchards in historic Fruita, and quiet desert trails that feel far removed from the busier parks to the west. If you’re heading toward Capitol Reef, my 2-day backcountry loop guide explores one of Utah’s quietest and most underrated wilderness routes.

Canyonlands National Park — Roughly 5.5 hours northeast – Take in sweeping views from Island in the Sky or hike the Needles District for a more remote experience.

Arches National Park — Around 5.5 hours northeast – Wander among over 2,000 natural stone arches, with short hikes to Delicate Arch and Landscape Arch.

If you’re heading south or west, the Grand Canyon anchors a very different style of road trip, with Sonoran Desert landscapes around Phoenix and Tucson and the stark basins and salt flats of Death Valley near Las Vegas. These destinations pair easily with a Grand Canyon visit, whether you’re building a short loop or a longer cross‑desert journey.

Phoenix, AZ — Just under 4 hours south Explore desert trails in South Mountain Park, visit the Heard Museum, or cool off in the city’s vibrant food scene.

Saguaro National Park — known for its towering cacti and sweeping desert views — lies about five hours south by car.

Chiricahua National Monument — About 6 hours southeast. Explore a maze of balanced rocks and towering volcanic spires on the Big Loop, which includes highlights like Echo Canyon and the Heart of Rocks. It’s one of the most dramatic landscapes in the Southwest and pairs well with a Tucson‑to‑New Mexico route.

Las Vegas, NV — Approximately 4.5 hours west – Recharge with a night of neon, catch a show, or detour to nearby Red Rock Canyon for a scenic hike.

Death Valley National Park — Another 2 hours west of Las Vegas. If you’re starting or ending your trip in Vegas, Death Valley makes an unforgettable detour, with otherworldly salt flats, narrow canyons, and sweeping desert vistas.