Missed Days 1-12 of the Pennine Way?

Day 13: A 22-mile leg on the Pennine Way Hadrian’s Wall route — from Greenhead to Bellingham, featuring Sycamore Gap and Roman history

Another long break brought us to Easter and a return to the north. After the trains fiasco the leg before, we were grateful for a lift from a friend. Despite the purchase of some decent new walking boots, I stuck to my old worn pair—not out of sentiment, but fearing blisters at the end of a huge 22-mile day, having only had the boots a week or two. Thirlwall Castle offered some quick history and excellent views before ascending and descending a large hill along the Pennine Way Hadrian’s Wall section—our first experience of the famous frontier.

The Pennine Way Meets Hadrian’s Wall

Built in Roman times on Great Whin Sill—a resistant igneous rock that eroded more slowly than the surrounding geology—the wall sits atop natural steep cliffs, separating the Scottish from the Roman Empire to the south. The trail follows the wall for eight miles, offering elevated views and a profound sense of connection to the past. Picnic benches at a lake near Burnhead offered a snack spot too good to pass up, though the cold wind across the water made it a brief stop. The trail undulates along the wall, passing roads and car parks, bringing the strange experience of walking amongst crowds on the Pennine Way.

Approaching Crag Lough, the trail rises and falls sharply some 80–100 metres above the surrounding terrain, but it’s fun walking with plenty of turrets and history to enjoy.

The famous Sycamore Gap tree was still standing when we walked, perfectly framed next to the wall in a natural dip. The tree featured in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, but was sadly cut down in a criminal act in 2023.

From there, the trail leaves the wall and heads north through pine plantations and moorland. It’s a long day, and we finished the walk in darkness—but with pub accommodation in Bellingham, all was forgiven.

Day 14: Bellingham to Byrness and beyond (17 miles)

A remote and rugged stretch of the Pennine Way from Bellingham to Byrness and beyond, featuring bog-hopping, forest plantations, and a sunset ascent into Scotland—where wild camping meets weary determination before a 27-mile push to the finish.

We had more good weather as the day began with an ascent out of Bellingham, through fields of sheep, then onto heather moor and yet more bog-hopping practice. Having stuck with my old boots, I had to do some serious jumping around — and despite drying them out in Bellingham, my feet were wet within the first few miles. Looking back, I’m amazed I didn’t buy those new boots sooner.

The views were far-reaching, but nothing stood out as particularly memorable. If I had a pound for every heather bush I saw, I’d be able to fund a large research grant into why they all look exactly the same. Sadly, they weren’t in flower — this being spring — so the visual reward was minimal.

The ascent up Padon Hill, then parallel to the forest plantation, was notable for the lack of an obvious trail and the need to drag ourselves through thick undergrowth.

I don’t think many people walk this section — and I can see why. At the top of the hill, a wide gravel path led us mile after mile through a monoculture conifer plantation, then along dusty roads where we dodged the occasional lorry thundering past with tonnes of logs — none of which showed the slightest interest in slowing down for a weary Pennine Way walker, unless perhaps to aim better.

The Pennine Way’s Log‑Dodging Olympics

This part of the country is remote, and accommodation is severely lacking. Unless you’re happy camping each night, it’s one of the major logistical barriers to walking the Pennine Way. So when we passed a campsite along the River Rede offering cheap showers, we were tempted to finish early — not because we were tired, but because the idea of standing under running water that wasn’t part of a bog felt almost decadent. But it wasn’t really a consideration — we’d already decided to combine the final two days into one massive 27-mile slog to the finish. The official website advises against it, but given the lack of roads, settlements, and amenities around here, it’s pretty much unavoidable.

We were pleased to pass Byrness and begin slowly eating into those remaining miles. After a long, steep ascent out of Byrness at the end of a long day, we enjoyed views of the sun setting over Catcleugh Reservoir.

With around an hour of daylight left, we pressed on, crossing the border into Scotland. And while PC Plod was unlikely to be lurking in the undergrowth waiting to pounce on rogue wild campers, we at least had the law on our side — not that it helped us sleep much, shivering in all three days’ worth of clothing as the cold night closed in.

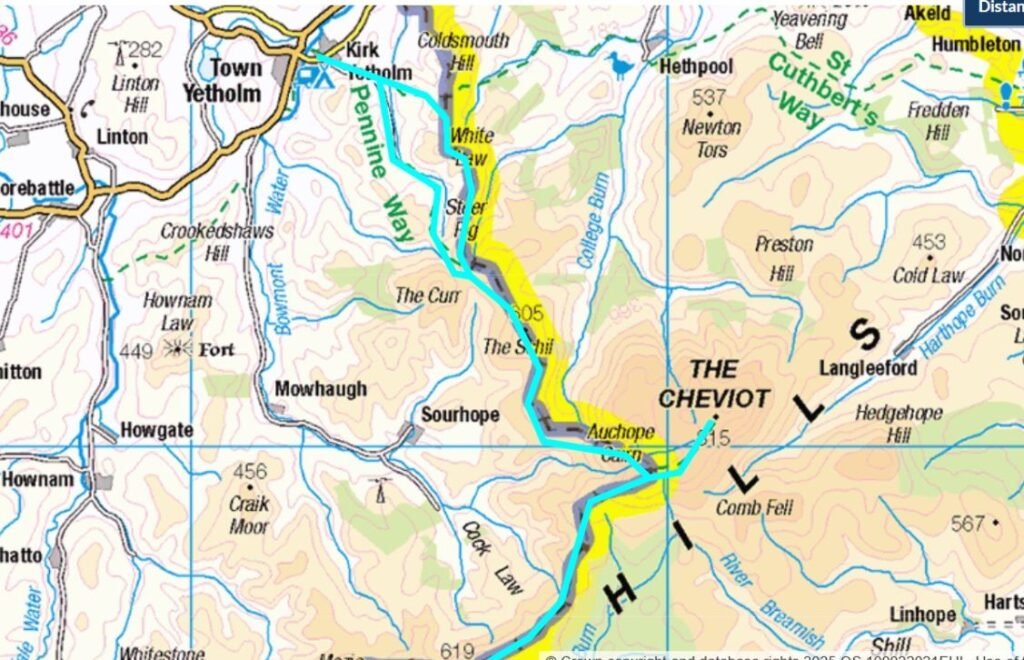

Day 15: Beyond Byrness to Windy Gyle, then Kirk Yetholm (25 miles)

We woke early, with a massive day ahead, to thick fog and weather best described as “atmospheric” if you’re writing a gothic novel. Conditions—both overhead and underfoot—were grim, and visibility was limited to a mile or so. We were clearly missing out on some impressive vistas, which we could only imagine in the abstract. It was a get-your-head-down-and-move day when it should have been views galore.

Windy Gyle did its best to live up to its name, and the noise was deafening as we ascended its spine. It’s an area I’ve since returned to on a crisp winter’s day (see below), to enjoy the views and see what we missed.

We skipped The Cheviot—having seen enough cloud for one lifetime, we didn’t need to go any higher. The cloud finally lifted above the peaks ahead, giving us an impressive descent towards the Refuge Hut. The landscape reminded me a little of Day 1 in Edale, but more rugged and with no company on the trail. In fact, we went two full days without seeing another soul, apart from the road crossing near Byrness the evening before. Still not done, the trail presented the worst bogs of the entire 268 miles, and we lost masses of time trying to stay upright and avoid plunging knee-deep into the moor.

Climbing The Schill was definitely mind over matter—mostly matter, by this point—but we still had miles to go and were thoroughly shattered.

Near Black Hag, the trail splits, presenting two options—we took the lower route hoping to dip below the clouds. In good weather, this would be an excellent stretch—one I must return to on a long summer evening, if I can bear the drive north. Conditions eased as we descended towards Kirk Yetholm, and we saw numerous deer racing into the distance, clearly unused to company and unimpressed by our pace. We completed the trail in pitch darkness, arriving in Kirk Yetholm just before 9 p.m.

The Border Hotel Diet Plan

We headed to the Border Hotel—though sadly not to enjoy a night’s sleep. Déjà vu struck, and it was Bowes all over again: we ordered drinks and requested a menu, only to discover the chef had switched the Border Hotel Diet Plan on at nine. More than a little miffed after a huge and cold day, we at least managed to secure a pudding. And we were presented with Pennine Way certificates — which I have no shame in admitting I was a little too proud to receive, though I must confess I was so hungry I briefly considered folding mine into a sandwich.

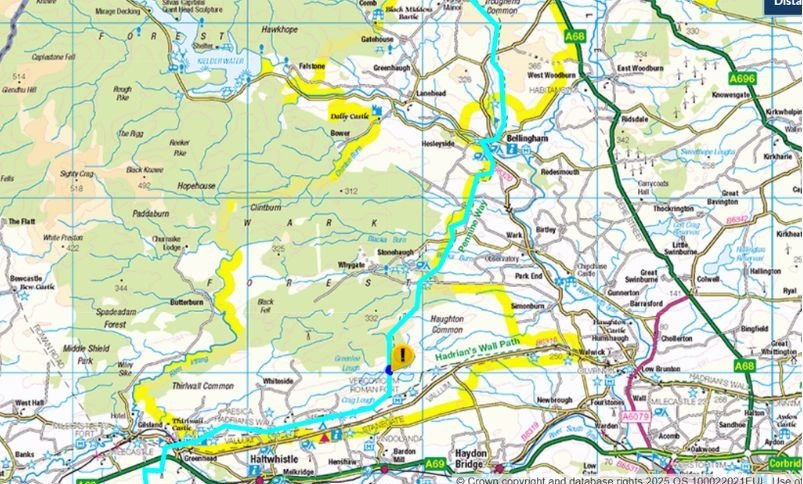

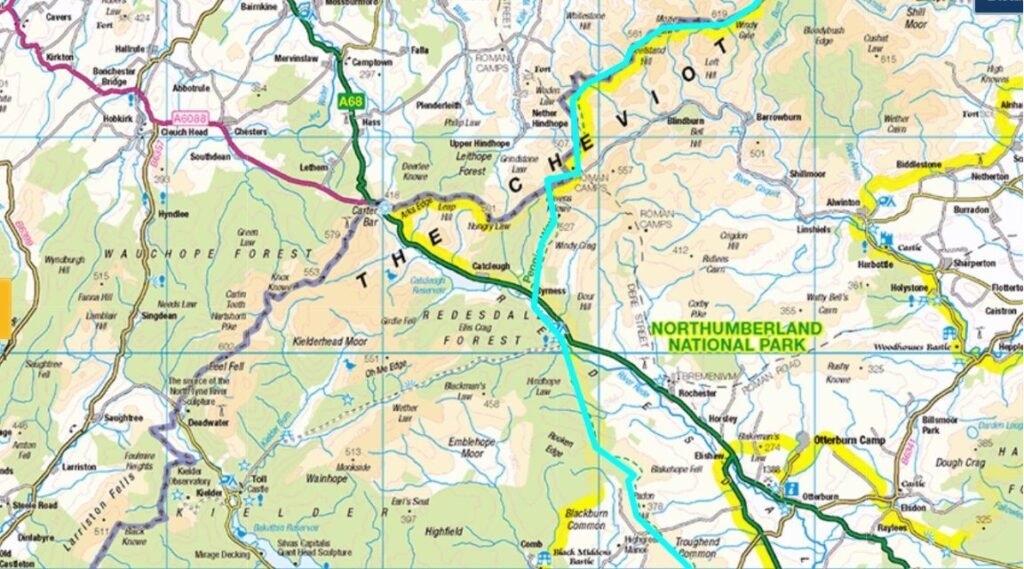

Pennine Way Route Maps | Days 13–15 Greenhead to Kirk Yetholm

Pennine Way: Greenhead to Kirk Yetholm: FAQs

How far is it from Greenhead to Kirk Yetholm?

Around 64 miles, usually walked over three or four days. Many hikers split it into:

- Greenhead → Bellingham (22 miles)

- Bellingham → Byrness (15 miles)

- Byrness → Windy Gyle or a refuge hut

- Windy Gyle / refuge hut → Kirk Yetholm (to avoid a single 27‑mile push)

What is the Greenhead to Bellingham section like?

A long 22‑mile day mixing Roman history, steep climbs, and dramatic scenery. You begin with Thirlwall Castle, then follow Hadrian’s Wall for eight spectacular miles before heading north through forests and moorland to Bellingham.

How difficult is the Hadrian’s Wall section?

Challenging but exhilarating. The trail rises and falls sharply along Great Whin Sill, often 80–100 metres above the surrounding landscape. It’s steep, rocky, and full of short climbs — but the views and history make it unforgettable.

What is Great Whin Sill and why does the Wall sit on it?

It’s a band of hard igneous rock that erodes slowly, creating natural cliffs. The Romans built the Wall on top of it for maximum defensive advantage and visibility.

Is Sycamore Gap Tree still there?

No. The tree was still standing when you walked the route, but it was felled in a criminal act in 2023. It remains one of the most iconic spots on the Wall.

Why does the Hadrian’s Wall section feel so busy?

Because it’s where three major long‑distance trails converge. The Pennine Way shares this stretch with both Hadrian’s Wall Path and the Coast to Coast Walk, meaning you suddenly go from days of solitude to crowds of day‑walkers, history lovers, families, and hikers from multiple routes. Add in car parks, tour groups, and the iconic scenery around Crag Lough and Steel Rigg, and it becomes one of the liveliest sections of the entire Pennine Way.

Are there any facilities between Bellingham and Byrness?

No. This is one of the most sparsely serviced parts of the Pennine Way. Byrness itself is tiny, with limited accommodation and no shops.

Why is accommodation difficult in this area?

Because the region is remote and sparsely populated. Unless you’re camping, you’re forced into long days — which is why many hikers end up combining the final two days into one huge push.

Can I detour to the summit of The Cheviot?

Only in good weather. It’s a worthwhile summit, but it adds time and effort to an already huge day.

What are the Cheviot Refuge Huts like?

Basic wooden shelters with benches and emergency supplies. No water, no heating, no facilities — but perfectly placed for breaking the final stage into two days.

What makes the final stretch of the Pennine Way so special?

Hadrian’s Wall, Crag Lough, Sycamore Gap (even without the famous tree), The Cheviots, Windy Gyle, the refuge huts, The Schill, and the feeling of finishing a 268 miles walk!